The interesting and spooky factoid comes from studies of tree-ring data that were used to estimate flows from the rivers that provide water to metro Phoenix and other parts of central Arizona.

As you might think, the freaky stretch of poor river flow doesn't bode well for the state's future.

"It's something that has not occurred since the 1300s," said Dave Meko, a research professor at University of Arizona's Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research. "This is unusual.""It's something that has not occurred since the 1300s." — David Meko

tweet this

The latest sign of climate calamity comes as Arizona continues to suffer from a 21-year period of abnormally low rainfall.

As the Arizona State Climate Office website explains, "drought is characterized by a string of drier than normal years, often interrupted by a few wetter than normal years."

The new and unwanted record that's been achieved is an unprecedented string of consecutive years of drier than normal years — without those wet-year interruptions.

Tree rings, as most school kids know, are layers of wood added in a tree's annual growing cycle. They can be studied to figure out things like how old the tree is and the weather the tree experienced during those years.

In 2008, U of A tree-ring gurus Meko and Katherine Hirschboeck studied tree rings from trees around the Salt, Verde, and Tonto rivers, using existing trees and those from obtained from archaeological structures. With the help of experts from Salt River Project, Meko and Hirschboeck were able to get a glimpse of the region's river flows from 1330 to 2005.

As with other studies, the 2008 study showed that the current drought isn't the most severe the region has seen in past centuries. Sometimes, the region receives long-term averages of low rain and snowfall for much longer than 21 years. Two medieval mega-droughts lasted for more than a century each.

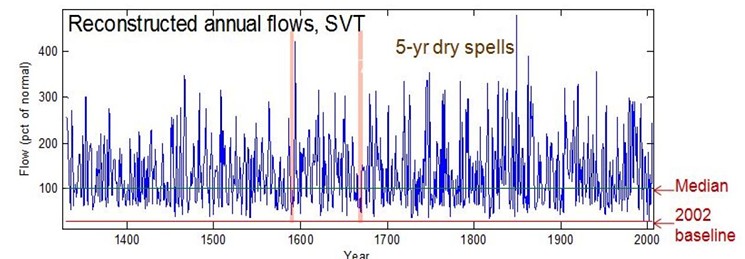

Yet even during those long droughts, the tree rings showed that the longest consecutive number of years with below-average river flow was five. In other words, for 670 years, the region could count on at least one good, wet winter with above-average runoff of snowmelt from the mountains for one year out of five.

Below-average river flow for five consecutive years occurred twice in the studied period, in the 1590s and the 1660s.

That five-year record has now been broken.

Chart showing the previous five-year streaks of consecutive years of below-average central Arizona river flows. The new record is six consecutive years, which occurred from 2010-2016.

University of Arizona Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research

It wasn't until earlier this year — the seventh year since the latest dry spell began — that a wet winter brought high-than-average runoff, he said.

An earlier study in 2005 by Meko and Hirschboeck that looked at the same rivers, plus the Colorado River basin, showed that when drought strikes the central-Arizona rivers, it also hits the Colorado River, and vice-versa. It proved that we can't count on one river system when the other delivers less water.

It also showed a couple of other bad signs that manmade global warming may be taking hold in recent times. The two single driest years out of the 800 studied weren't during the megadroughts — they were in 1996 and 2002.

The recent six-consecutive-year dry streak also appears to be evidence of the modern climate change, Meko said.

"It fits into what people think is happening," he said.

No break from the drought appears to be in sight, unfortunately.

Although above-average rain and snow fell during the winter of 2016-2017, breaking that streak of six consecutive below-average years, it was followed by one of the driest monsoon seasons and autumns in 120 years.

In Phoenix, a 103-day spate of dry weather just ended on Tuesday with a smattering of rain.

Experts believe that drying trend will most likely continue through next years.

"The consensus forecast is for a greater chance of a drier than normal winter," Ester said. "In our past, fall seasons that were this overwhelmingly dry tended to have below-normal winters. There were exceptions, so I’m planning for dry but I won’t give up on a good winter until much later, like the end of February.”

Dino DiSimone, water supply specialist for the U.S. government's Natural Resources Conservation Service, agreed that below-average rain and snow was probable, though not definite, in the coming months.

Lake Mead, which stores Colorado River water for the river system and Central Arizona Project canal in Arizona, is currently at 39 percent of capacity, DiSimone noted. While that's slightly higher than last year, if this winter doesn't defy the odds and produce lots of snow and rain, Lake Mead's capacity could drop to worrisome levels next year. That, in turn, could trigger a reduction in water allocations for 2019 in Arizona — a prospect that the state escaped only narrowly this year.

"We were getting in a better condition, but now with below-normal [precipitation], we're sliding back into a more dire situation with our water-storage reservoirs," DiSimone said.