Why the tide of freedom and democracy has started to ebb, and what can be done about it.

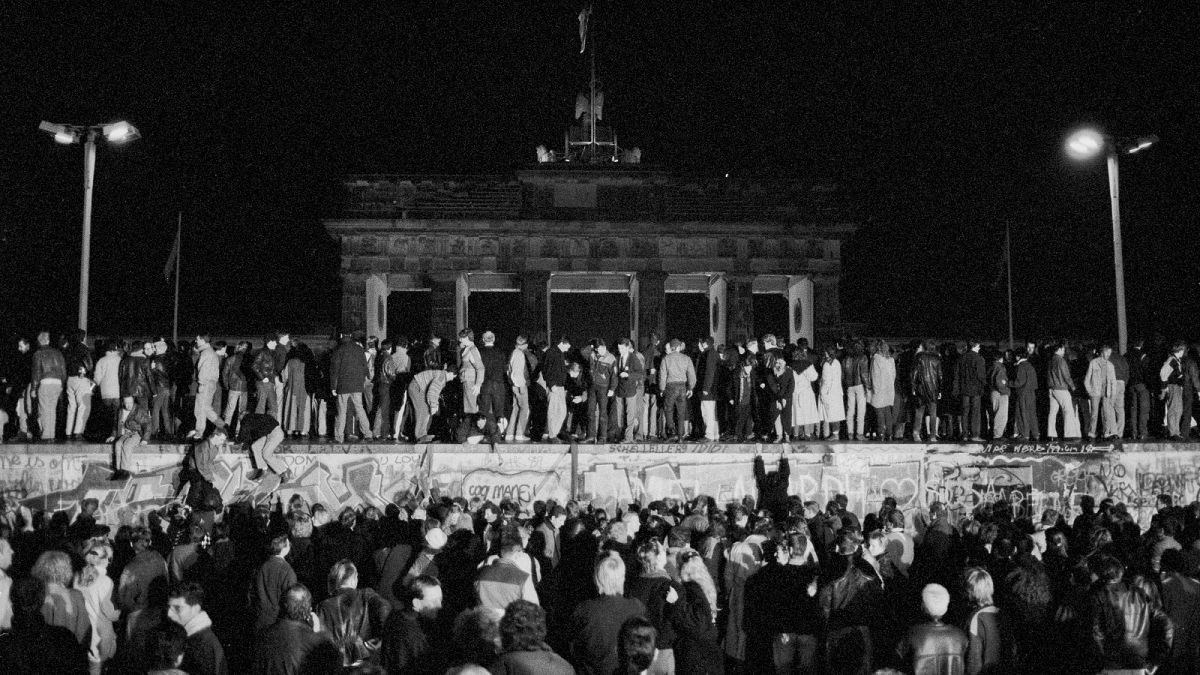

It wasn’t meant to be like this. When the Berlin Wall crumbled 30 years ago this Saturday — bringing down the totemic symbol of Soviet control in Europe, and making the United States the world’s sole superpower — the great ideological debate seemed to have been settled. A system of government based on individual rights and mass enfranchisement had proved itself to be the best. Democracy had won.

Those were heady days. Throughout the West, there was a rush of excitement as Poland, then Hungary, then Czechoslovakia and finally East Germany freed themselves from authoritarian rule and won democratic rights. Scholars pontificated aboutwhether history might be coming to an end because the battle over how countries were to be governed had finally been settled. As a politics undergraduate in the fall of 1989, I was caught up in the exhilaration of the moment, especially when I met some of the young pro-democracy campaigners, including an impressive Hungarian activist named Viktor who seemed to be going places.

The pro-democracy tide continued through the 1990s as post-Soviet states from Georgia and Ukraine to the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania all gained their freedoms. It wasn’t always bloodless, demonstrated most tragically in the former Yugoslavia. But the tide was only going one way: When the wars in Bosnia and Kosovo ended, elections followed soon after.

Well into the 2000s, the advance of democracy seemed unstoppable. Throughout Africa, much of Asia - from former Soviet States like Kazakstan to former US-backed dictatorships like Indonesia - Latin America and even parts of the Middle East such as Iraq and Lebanon, people seemed to be winning an ever-greater voice in determining their own governments. And it wasn’t just elections that were becoming more widespread, but other democratic institutions, too: a free press, an effective judiciary, anti-corruption safeguards.

Then something changed. Starting around 2006, the number of countries that could be counted as democraticplateaued, and even started to fall. Around the world, indices that measure electoral pluralism, civil liberties and the functioning of democratic institutions went into reverse. Democracy had gone into retreat.

When first noticed, the trend was mostly mistaken for a statistical blip. Democracy’s advance was considered as automatic as its appeal to the people it empowered, so Russian tanks taking control of Georgia by force in 2008 andRwanda and Uganda introducing authoritarian controls were dismissed as anomalies.

But the worldwide decline in democracy since the mid-2000s is now too obvious to deny; the facts can’t be described as anything other than a trend. This doesn’t mean democracy is doomed — democratic progress has been undone before, most darkly in the 1930s but at other times, too,and always rebounded with fresh vigor in the yearsafter.

Nevertheless, there are strong reasons why the retreat of democracy should worry us greatly. It means power is ebbing from a tried and trusted form of government — one which has brought peace and prosperity to the world. That power is being grabbed by charismatic autocrats and kleptocrats who win office democratically and then start rewriting the rules, or who just go ahead and steal it. The American model of government is being shelved, along with affinity to the United States in several countries.

So, what went wrong? And can democracy be saved?

There are several explanations for why democracy has faltered, some more plausible than others. Changes in culture and technology may be a factor. The decline in democracy coincides with the arrival of the first iPhones, ushering in a worldwide shift from people receiving news through national broadcasters — which have tended to unify opinion — to social media, which tend to polarize populations. Technology, and the internet in particular, has enabled dictators and authoritarian regimes to ostracize dissent, push propaganda and generally control information.

But the internet has also facilitated democratic uprisings, including the 2011 Arab Spring and color revolutions around the world (so named because protestors adopted a color to unify their cause, from orange in Ukraine to saffron in Myanmar to pink in Kyrgyzstan). The relationship between technology and democracy is best described by the Facebook status “It’s complicated”; technology alone certainly does not explain the trend.

Could it be that democracy is ill-suited for the problems of today? A system based on national elections every four or five years works best when painful decisions reap results within a country’s borders, and within the time frame of the electoral cycle — not ideal when tackling global climate change or long wars or globalization.

But again, this is only a partial explanation. Few of these problems are new, and democracy itself can adapt; most dramatically, it evolved from the direct democracy practiced in ancient Greece to the representative democracy popular since the Industrial and American revolutions of the late 1700s.

A more promising argument revolves around money. Although democracies are generally rich, it’s not clear thatdemocracy actually generates wealth. There’s more evidence that thecausation works the other way: When countries pass a certain threshold of income (estimated at about $10,000 per head), demands for democracy increase sharply. Below that threshold, non-democracies might actually grow faster and even have more popular appeal because stability can boost growth more than freedom in these societies.

Authoritarian China, for example, has developed a model of public decision-making that gauges and then reacts to public concerns; in other words, government that is as responsive and capable as a middle-order democracy, but without being remotely democratic. And democracy is something very few Chinese citizens are demanding publicly, except for those in Hong Kong — one of the few parts of the country with a per capita income well above $10,000, as well as a legacy of democracy from its time under British rule, which many in Hong Kong fear is now threatened by Beijing.

Moreover, China has been able to export its nondemocratic model throughout the world, providing an alternative to democratization to countries that want to develop economically, by offering aid and largesse that has helped authoritarian governments hold on to power. Worse, it has blunted efforts by the United States and its allies to promote democracy, especially those that tied development assistance to improvements in accountability, transparency or other democratic metrics. In 2013, President Evo Morales of Bolivia made the shocking decision to expel USAID and its entire relief program so as to escape the relatively minimal democratic conditions the U.S. had placed on its money. He could take cash from Beijing instead, which came with far fewer strings attached.

China has received a heavy assist in reversing the wave of democracy by the other major counter-lever to American global power: Russia. To start with, it exemplified the shortcomings of democracy in poor, unstable countries; the country’s experiment with democracy in the decade after the Cold War failed, as many Russians came to associate that mode of governance with poverty, corruption, severely reduced life expectancy and national humiliation (that the experiment was founded on the deep hostility to western democracy embedded in the Soviet Union didn’t help). Today, while China undercut Western moves to support democracy, Russia attacks them outright.

In the most obvious cases — Ukraine, Georgia and Montenegro — Russian President Vladimir Putin sent in tanks and paramilitaries to undo elected governments. But it has also ran a much broader subversion campaign in more than 40 countries: funding destabilizing political startups, spreading false stories to stoke divisions and using cyberattacks to undermine institutions. Russiahas “weaponized” immigrants from Syria to disrupt democracy throughout Europe, deployed anti-democracy tacticsthroughout Africa and propped up autocrats in Latin America and Asia. Unlike Kosovo and Bosnia, don’t expect the war in Syria to end in free and fair elections if the Moscow-backed dictator, Bashar al-Assad, snuffs out the opposition. And some of the tools being used to attack democracy nowmay be more potent than ever.

Which takes us back to Viktor, to whom I once gave instant coffee in my dingy student dorm, and who has transformed himself from a young anti-authoritarian into the populist prime minister of Hungary, a position he’s held for 13 of the 30 years since I met him. Viktor Orban is unafraid to adopt the authoritarian tactics he once railed against —closing universities that foster dissent, directing tax inquiries into his foes, consolidating media ownership under his own influence and directing government funds to entrench the power of his ruling party. It’s democracy, perhaps, but not as we know it. Orban himself has adopted the phrase “Illiberal democracy.”

Orban’s political journey has followed an almost literary arc, from fighting for freedom to fighting against it. I remember getting the sense, in 1989, that he was determined to change the system so he could get things done. That drive has never changed, even though the direction of it has pivoted 180 degrees — perhaps not coincidentally, allowing him to stay in power to keep getting things done his way.

Orban’s model of government emulates the one that Putin, rather than Thomas Jefferson, has charted: He is elected, but through a process in which voter choices were both limited and guided very heavily, including through biased state media. And, like Putin, he is committed to rolling back the freedoms and rights on which the best democracies are built. It is a common formula, one which has also taken root in Turkey, Cambodia and Egypt — places which, alongside Hungary, have dropped several notches in the international democracy rankings in recent years.

History offers us conflicting lessons as to how best to rekindle democracy. Democracies have been knocked down before — by autocratic monarchs, economic crises, home-grown ideologies and foreign invasions — and often come back reinvigorated, as the people express an overwhelming will to ensure that episode can never be repeated given how painful the experience of non-democracy was. After all, one of democracy’s great virtues is the ability to learn and adapt — reform can be as simple as electing a different government. But that rebound can take many years, and is sometimes tragic and bloody. Just ask a veteran of the failed ‘Prague Spring’ of 1968, which was savagely suppressed for 21 years before the country returned to being the democracy it had been before the German occupation in World War II.

For countries on the front line of the threat, such as Estonia, whosedemocracy has been actively sabotaged by Russia, internal reforms to protect against meddling are not enough. To be safe, an alliance of democracies needs to circle the wagons, aware that when one country becomes less democratic, neighboring countries are weakened in turn.

Elsewhere, the business of protecting democracy can be tortuous: It’s about slowly building up the fabric of a nation’s institutions— training journalists to ask tough questions, teaching political parties to campaign, keeping the judiciary independent — so they can act as they should when a crisis comes.

As Jefferson himself warned, “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” Democratic rights need to be treasured; they are far more easily given up than regained.

- Iain King, CBE, is the UK Visiting Fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. An experienced diplomat and academic, he is the author of several fiction and nonfiction books on history and international affairs

This piece was first published by NBC Think.

____________

Are you a recognised expert in your field? At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.